John Debrett was born on 8 January 1753, the son of John (born Jean, a French cook), and Rachel, née Panchaud. His father lived near the Melbury Park estate in Dorset, where he worked for the Earl and Countess of Ilchester, but John Debrett was baptised in Westminster and therefore may have been brought up by his mother in London.

At the age of 13, John was apprenticed to ‘Robert Davis, bookseller etc’ of Piccadilly, on payment of the premium of £10, and so began the career that would eventually link his surname with the nation’s second estate for centuries to come.

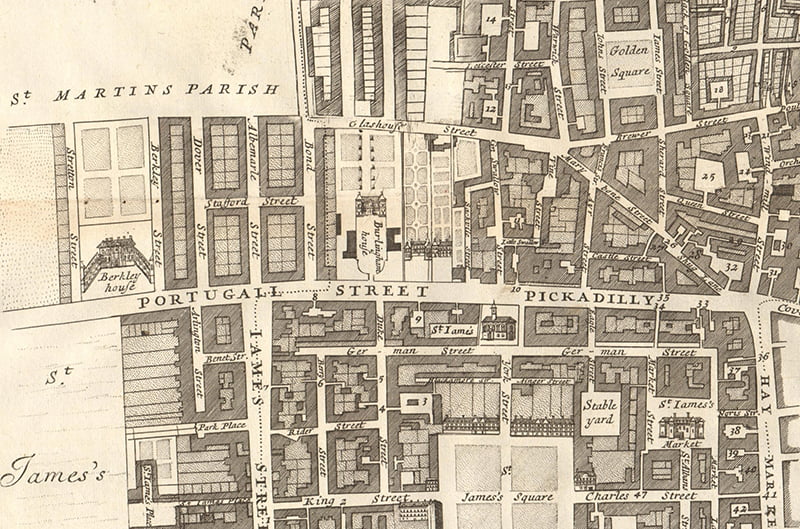

Eighteenth-century Piccadilly was the home of numerous booksellers, printers, engravers, playing-card makers and print sellers. Robert Davis was in business at No. 50, on the western corner of Sackville Street, and his business was continued after his retirement in 1772 firstly by his son William Davis, who died eight years later, and thereafter by his daughter Mary, who died unmarried in 1792.

Shortly after William Davis’s death, John Debrett placed an advertisement in the London Courant, advising ‘the Nobility and Gentry, and his friends in general, that he is removed from the late Mr William Davis’s, the corner of Sackville Street, to Mr Almon’s, bookseller and stationer, opposite Burlington-House’.

John Almon was a radical journalist, bookseller and publisher of 178 Piccadilly, formerly a private house, which became a lively hub for Whig politicians and sympathisers. In 1781, the 43-year-old Almon retired (temporarily, as it turned out). In his own words,

‘… he quitted his business, in favour of a very worthy and respectable young man… and went into the country.’

The ‘worthy and respectable young man’ was John Debrett.

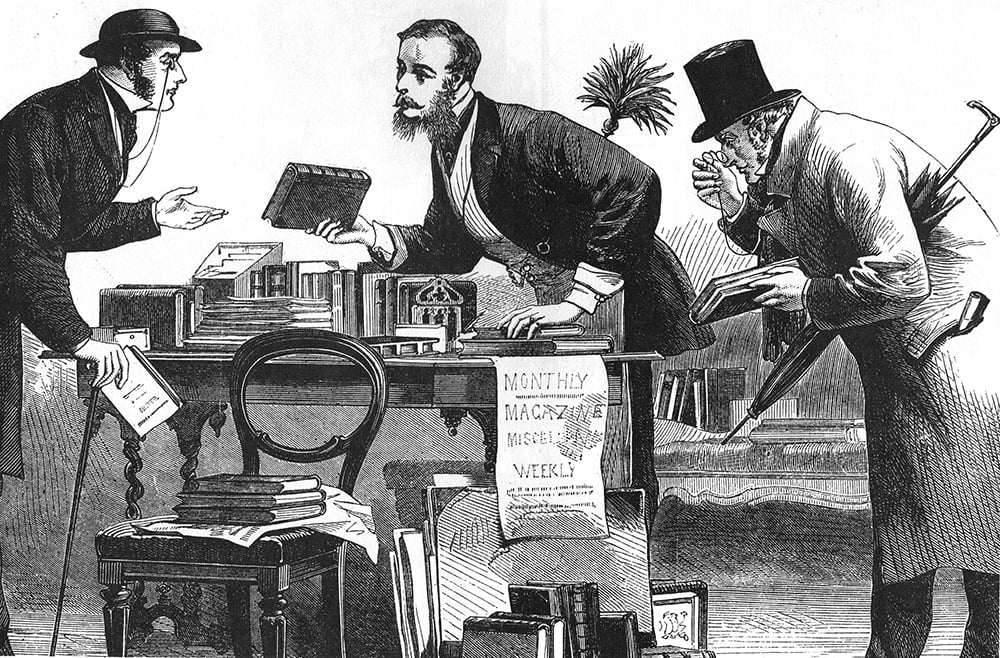

During John Debrett’s career, the book trade was in a state of vibrant growth. Literacy levels had increased and there was a seemingly boundless hunger for newspapers, journals and political and literary writings of all kinds. Debrett’s closest rival was his contemporary John Stockdale, and an anonymous biographical article contains an account of a lively argument between the two men in Debrett’s (formerly Almon’s) shop. However, in the 1780s and 1790s Debrett and Stockdale appear to have exercised some degree of co-operation. The two men were certainly close neighbours in Piccadilly.

Debrett’s list was an eclectic one. In January 1782 he co-published The European Magazine, and London Review, a new venture by the Philological Society of London. From 1780 to 1803 he continued John Almon’s important work of publishing the Parliamentary Register and other raw political material of the day. Official documents such as commissions on the state of the nation’s land, water meadows and draining peat bogs, also had a place in John Debrett’s list, as did miscellaneous items such as a guide to ornamental gardening and Maternal Letters to a Young Lady on her entrance into Life (2s).

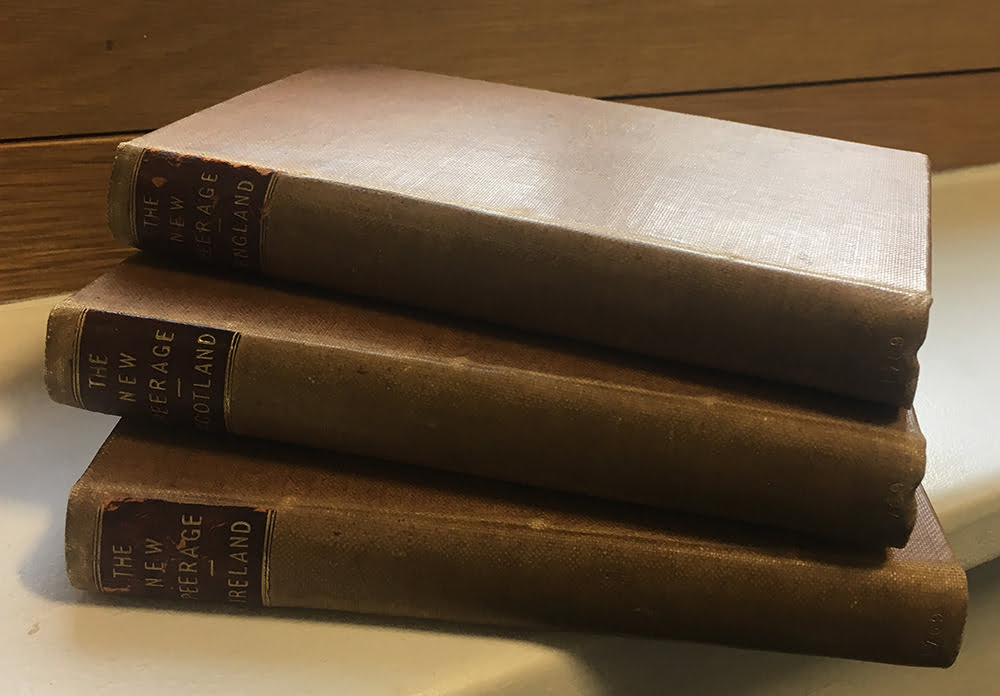

In 1769, a new three-volume work was published with a weighty title: The New Peerage; or, Present State of the Nobility of England, Scotland, and Ireland, containing an account of all the Peers, either by tenure, summons, or creation, their descents and collateral branches, their births, marriages, and issue, also their paternal coats of arms, crests, supporters and mottoes, to which is added a list of the extinct peers, and an account of the chief governors of Ireland. The editor was not named, but is thought to have been John Almon. It was this work, that would pass through numerous changes of shape and form to become, 250 years later, the present 150th edition of Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage.

A second edition of John Almon’s New Peerage was published in 1778 and in 1784, a third edition was published which now bore the name of J. Debrett. The fourth edition appeared in 1790 in three volumes, but the Peerage then appears to have lain dormant for twelve years while Debrett turned his attention to a wide variety of other publications.

By 1802, John Debrett was firmly established, not particularly as a chronicler of the aristocracy, but as a notable London bookseller. In this year, a tourist guide entitled the Picture of London listed ‘Debrett’s, Stockdale’s, Wright’s and Hatchard’s’ in Piccadilly among those west end booksellers ‘furnished with all the daily newspapers, which are much frequented about the middle of the day, by fashionable people, and are used as lounging-places for political and literary conversation.’

It was in 1802 that Debrett brought out the next incarnation of what had once been Almon’s New Peerage, and his name was now sufficiently well-known to be a selling point: it would hereafter be known as Debrett’s Peerage.

Debrett’s reinvention of his Peerage publications in 1802 may also have had a more pressing motive. By the end of 1801, the year before the first Debrett’s Peerage appeared as such, his fashionable Piccadilly shopfront masked a darker reality. John Debrett was in serious financial difficulties.

John Debrett was declared bankrupt on 31 October 1801, and he disappears from the lists of London publishers and printers after 1803. A lengthy process of attempting to settle with creditors ensued.

With debts of £1,435, Debrett was committed to the relative peace of the King’s Bench prison, and discharged on 1 February 1806. In the meantime, his wife Sophia was listed as the tenant of the double premises in Piccadilly. On 17 November 1814 he was discharged from The Fleet, where he had again been imprisoned for bankruptcy. He was now in his sixties and, according to his obituary, a close relative enabled him to retire by providing him with a small annuity, although he continued editing until his death in 1822.

It was the firm of Rivington, of St Paul’s Churchyard, who published Debrett’s Peerage in these last years, assisted in editorial matters by Francis Townsend, Rouge Dragon, the College of Arms being very near at hand. In the 1819 edition, Debrett included an editorial note dated 11 January of that year with the address ‘29 Fetter Lane, Holborn’, which is close to Fleet Street.

John Debrett was found dead at his lodgings in Upper Gloucester Street, Regent’s Park, on 15 November 1822. His obituary in Gentleman’s Magazine was brief and sympathetic:

Nov.15. At his lodgings, Upper Gloucester-street, Regent’s Park, Mr John Debrett. He had been for some time in a declining state of health, and was found dead in his arm-chair by the side of his bed. He was formerly a very eminent Bookseller in Piccadilly, where he succeeded the well-known John Almon; and his shop was the general resort of gentlemen of the first consequence in the Whig interest, and in opposition to the measures of Mr Pitt; whose friendly admirers at the same period were daily to be found in the shop of his neighbor Stockdale.

Mr Debrett was a kind, good-natured, friendly man, who experienced the vicissitudes of life with fortitude. He had full opportunity of acquiring a large fortune, but from too much confidence and easiness of temper, he did not turn it to the best account. After several years attention to business, he was compelled to retire from it on a small annuity settled on him by a near relation; and the latter part of his life has been actively passed in the useful employment of compiling some valuable publications, particularly various editions of the Peerage and Baronetage.

Debrett was laid to rest with his father in the burial ground of St James, Hampstead Road, on 22 November 1822, aged 69. He left no will.

Thus the bookseller and publisher John Debrett died alone, without wealth or honours, working until the end of his life on the publication that was to carry his name – he might have been surprised to learn – so far into the future.

This is an abbreviated version of Dr Susan Morris‘s special article in the 2019 edition of Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage.